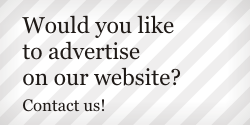

Johann Baptist Wanhal (Jan Křtitel Vaňhal)

(1739-1813)

Public perception of Johann Baptist Wanhal (Jan Křtitel Vaňhal) a preeminent Viennese composer (a Czech of Vienna) of the eighteenth- and early nineteenth century has changed little since he died in Vienna on August 20, 1813. The biographical articles in the two most important musical dictionaries, Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (1951) and The New Groves (1980) were based upon the same sources. So too were the incidental articles written subsequent to Wanhal’s death.

They reflect the questionable comprehension and biases of the original contemporary authors: Charles Burney, whose single visit with Wanhal occurred in 1772, Gottfried Johann Dlabacž, Wanhal’s Bohemian compatriot who stayed with him in Vienna for an extended period of time in 1795, and an anonymous Viennese author whose necrology seems to have been partially based upon rumor and to have been further influenced by the interpretations of German authors such as E.L. Gerber and J.F. Rochlitz.

These authors agree in general that Wanhal was born in bondage to the family Schaffgotsch in the town of Nechanice, in the Hradec Kralové area of Bohemia, today’s Czech Republic. There his favorite teacher, Anton Erban, taught him to play the organ. Much of the first twenty years of his life was spent in nearby towns where he was trained to sing and to play string and wind instruments. He also was sent to Marscherdorf where he learned German and other subjects in order to prepare himself for moving to Vienna. At the age of 13 Wanhal became organist in Opocžno (Opočno). He later became choir director in Hniewczowes (Hněvčeves) in the province of Jičin. Here he met Mathias Nowak, an outstanding violinist who trained him to be a virtuoso violinist and to write concertos. With the help of the Countess Schaffgotsch Wanhal moved to Vienna in 1760-61. A brilliant and attractive young man he immediately flourished. He freed himself from bondage, and in less than ten years he composed at least 34 symphonies and was recognized as one of the most important symphony composers of the time. In 1769 the nouveau riche and ambitious Baron I. W. Riesch of Dresden who wanted to start his own musical establishment visited Vienna in search of a suitable Kapellmeister. Riesch was so impressed with the young Wanhal that he financed an extended stay in Italy where the young novice could socialize with and learn from the best composers and experience the atmosphere of the great aristocratic courts.

However, when he returned to Vienna after more than a year of luxurious living and traveling in Italy, Wanhal declined the Kapellmeister position. There is no record of his reason for having done so, but it was alleged that he went mad and burned some of his compositions and never fully recovered his creative powers. That rumor was embellished by some German writers who were unacquainted with Wanhal’s compositions but wrote that Wanhal was overcome by a debilitating mental disease and that his remaining compositions were weak and uninteresting. It has its source in Burney’s statement (in his famous “Travels…“ of 1772) that a ‘little perturbation of Vanhal’s faculties’ had caused his compositions to become ‘insipid and shallow’ – a curious statement in view of Burney’s later observations to the contrary! Regardless, the harmful effect of Burney’s remarks on Wanhal’s reputation outside Vienna was profound and long lasting.

Prof. Paul Bryan has devoted many years to studying Wanhal. His investigations show that the impression given by Burney was false, and that, to the contrary, Wanhal was astute and resourceful. For several years after returning to Vienna and with the help and collaboration of the powerful Count Ladislaus Erdödy, Wanhal, a recluse, lived and travelled sporadically between Vienna and Varaždin in Croatia, the seat of one of the Count’s palaces. During that time he continued to compose symphonies, chamber music (including string quartets) and music for the church.

In the late 1770s, in response to the changing musical tastes of the Viennese public, he ceased composing symphonies and, a few years later, string quartets, and began to cultivate the unique opportunities offered by the fledgling Viennese music publishing industry; thereby he could control the character and dispersal of his works. Viennese publishers subsequently issued more than 270 prints of his music. At this time the focus of Wanhal’s composing shifted away from the nobility, fewer of whom could afford to support an orchestra, and more toward the public (whose interest in keyboard music was rapidly rising). He continued to compose serious music, such as concertos and works for the church, but he concentrated principally on a wide variety of music for and with keyboard. He also wrote many pieces for the entertainment and instruction of the public, including some historically-based program music such as ‘Die Schlacht bei Würzburg’ which drew sarcastic remarks from critics in Germany.

Most of Wanhal’s church music (at least 250 works including 48 masses) remains unstudied and unpublished, and little is known about it other than the names of the churches and monasteries that appear on the title pages. However, after he examined two of Wanhal’s late masses, Rochlitz (a well-known German specialist of Bach, Haydn, and Mozart) endorsed their high quality. But the tenor of his remarks show that he was little acquainted with Wanhal’s serious compositions and that he was predisposed to disparage them – thus demonstrating the lingering effect of Burney’s remarks in his famous “Travels” of 1772.

«Judging from this valuable work (in church music), Vanhal in his later years lost nothing in imagination and art – as one might maintain with his later instrumental compositions; in every respect he had gained much more. Here the ideas are more original; imagination, understanding, and taste are respectable, and the work is far more thorough (also with respect to counterpoint and fugue) than he is given credit for even in his best symphonies from the earlier period.»

Wanhal is a shadowy figure; only part of his vast output of music has been satisfactorily evaluated or even catalogued. My studies of Wanhal and his symphonies confirm Alfred Einstein’s statement to me that “Wanhall was a very influential man with international fame; you certainly would find traces of his symphonic work on the next generation.” As his career unfolded, Wanhal with his independent spirit and apparent lack of concern for his reputation in future society, became one of Vienna’s most important and influential citizens, a highly respected freelance composer, teacher and performer, a role model. It is difficult to assess Wanhal’s role as an entrepreneur and example to others like Mozart. But he was clearly one of the first big-time composers who broke from the typical sitting-below-the-salt position at a rich person’s table (as did, e.g., Wolfgang Mozart and Joseph Haydn), and supported himself by teaching, performing and composing on commission or for publication. The extent of his influence is difficult to determine but there is no doubt that Wanhal was one of the leaders, indeed a pioneer, as well as a facile composer who produced first class symphonies and chamber music as well as large quantities of smaller pieces for entertainment or instructional purposes.

How to assess his influence? His role as a teacher in Vienna is acknowledged by many. His most famous student was Ignaz Pleyel, who eventually became an adored composer and editor whose career took him to Paris where his name is still venerated on one of the best-known concert halls: the famous Salle Pleyel on Paris’s rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré, no. 252. And who can doubt that Mozart was very aware of Wanhal’s debt-free existence?

In conclusion, Wanhal was one of the leading composers of the era of Classicism and the earliest stages of Romanticism. His compositions were performed throughout the world and numerous printed editions of his works appeared in his lifetime. Boldly original and possessed of formidable powers of invention, Wanhal was highly regarded by his professional colleagues, including Haydn and Mozart both of whom performed his works and on one famous occasion joined with him and Dittersdorf to form the most distinguished string quartet in the history of music!

Paul Bryan Professor Emeritus Duke University (USA) and author of Wanhal’s symphonies catalogue