ALLAN BADLEY

Social dancing, in both the public and private spheres, was an integral part of life in Vienna in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, dancing was so much part of the cultural landscape that it was even the subject of a number of imperial decrees aimed at its regulation. In her recent book, The Viennese Ballroom in the Age of Beethoven, Erica Burman draws particular attention a decree issued in 1772 that opened the two imperial ballrooms (the large and small Redoutensäle) to the public for masquerade balls1. Anybody could attend these events, regardless of social station, with the exception of servants wearing livery. Masquerade balls were only permitted in the imperial ballrooms and the wearing of masks in any other dance hall or other public place was forbidden.

Dancing itself was to some extent an incidental activity at the masquerade balls. People attended them for a variety of reasons: to admire the costumes, to meet friends, eat, drink, gossip and to listen to the music. For members of the nobility, as Joonas Korhonen observes, it was these activities rather than dancing which drew them to the masquerade balls. Indeed, ever since the opening of the imperial ballrooms to the public and its attendant risk of inadvertently dancing with members of the lower classes, social dancing, for the nobility, became an activity best pursued at private balls2.

The masquerade balls held in the Redoutensäle were the most elaborate public dances in Vienna and were the most impressive in terms of the music performed. During the 1790s,many of the most distinguished composers in Vienna contributed music for the Redoutensaaldances, among them Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Koželuh and Wanhal. However, many other composers were also active in the sphere, some of whom appear to have specialised almost exclusively in the composition of dance music. Much of this music has survived, preserved as part of the Kaisersammlung and now housed in the Austrian National Library, but with the exception of the dances composed by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, it has not attracted a great deal of attention from either musicologists or dance historians. While Buurman’sresearch and that of figures such as Korhonen and Reingard Witzmann3 has shed valuable light on many aspects of dance culture in Vienna, much remains unknown. For all the material evidence that survives for the Redoutensaal dances, we cannot even be certain how the music was performed and, by extension, how it was danced to. In spite of occasionalreferences in diaries and letters to their writers attending the masquerade balls at the Redoutensäle, only one description exists of how the balls were conducted. In his 1816 Beschreibung der Haupt- und Residenz-Stadt Wien, Johann Pezzl notes that “the orchestra in each ballroom alternately plays an hour of minuets and an hour of German dances”.4 While Pezzl’s account helps to explain the sheer volume of dance music composed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as well as the dominance of the minuet and German dance, it adds nothing to our knowledge about their performance. For that, we must turn to the music itself in order to speculate how these dances were executed. The dances composed by Johann Baptist Wanhal for balls in 1792 and 1794 offer excellent case studies in this respect as well as allowing us to consider some of the compositional strategies he employed to create musical variety in a medium that offered little scope for originality.

One of the many things that is unclear about the masquerade balls is how and why the various composers were commissioned to write music for them and what factors determined whether their dances would be performed in the large or small ballroom. As Table 1 illustrates, high-profile composers were not automatically assured of their works being performed in the large ballroom. In 1791, for example, Johann Baptist Haselbeck dominated the large ballroom while Mozart’s dances were performed in the small ballroom. The following year, Wanhaland Joseph Triebensee composed dances for the small ballroom while Haydn’s minuets were performed in the large ballroom for the Artists’ Pension Society Ball. This annual event, which fell outside the carnival season, was considered one of the musical highlights of the year,5 yet in 1793, dances by Mozart and Haydn were performed in the small ballroom while Leopold Koželuh’s minuets and German dances were performed in the large ballroom. As a final example of how difficult it is to understand the rationale for these choices from the modern perspective, it was Franx Xaver Süßmayr who was accorded the honour of composing dances for the large ballroom at the Artists’ Pension Ball in 1795 and Beethovenwhose dances were relegated to the smaller room. Since the decision presumably rested with the music director, any number of reasons might have applied ranging from personal favouritism to the likely audience for the dances. Perhaps the small ballroom traditionally attracted a more discerning audience.

LRS (Large Redoutensaal) SRS (Small Redoutensaal) APB (Artists’ Pension Ball)

Figure 1: Dated Redoutensaal Balls 1791-1795

|

Year

|

Venue

|

Composer

|

Deutsche

|

Menuetti

|

|

1790

|

LRS

|

J B Haselbeck

|

12

|

12 + 6 Trio

|

|

1791

|

LRS

|

J B Haselbeck

|

12 + Coda

|

12 + 6 Trio

|

|

LRS

|

J B Haselbeck

|

12

|

||

|

LRS

|

J B Haselbeck

|

24 (12 x 2?)

|

||

|

SRS

|

W A Mozart

|

12 + 12 Trios

|

||

|

1792

|

J B Wanhal

|

24 (12 x 2) Trio/Coda

|

24 (12 x 2)

|

|

|

J Triebensee

|

||||

|

LRS (APB)

|

J Haydn

|

12 + 11 Trio

|

||

|

|

LRS |

J Heidenreich |

12 + 3 Trio/Coda |

|

|

|

SRS |

Unknown |

|

12 |

|

25/11/1792 |

SRS |

Unknown |

|

6 |

|

25/11/1792 |

? |

Unknown |

|

12 |

|

25/11/1792 |

? |

Unknown |

12 |

|

|

1793 |

SRS |

T Weigl |

12 + 12 Trio/Coda |

12 + 12 Trio |

|

|

SRS |

F X Süßmayr |

|

12 + 12 Trio |

|

|

LRS (APB) |

L Koželuh |

15 |

12 |

|

|

SRS (APB) |

J Haydn Mozart |

|

|

|

1794 |

SRS |

J B Wanhal |

12 + 12 Trio/Coda |

12 + 12 Trio |

|

|

SRS |

J Triebensee |

12 + 12 Trio/Coda |

|

|

|

LRS (APB) |

P Ditters von Dittersdorf |

|

|

|

|

SRS (APB) |

J Eybler |

|

|

|

1795 (22/11) |

LRS (APB) |

F X Süßmayr |

12 |

12 |

|

|

SRS (APB) |

L van Beethoven |

|

|

|

|

SRS |

J Eybler |

|

12 + 12 Trio |

|

|

SRS |

J Weigl |

12 + 12 Trio/Coda |

|

|

|

LRS |

J B Haselbeck |

12 + Coda |

|

Nominal responsibility for the imperial ballrooms lay with the administration of theHoftheater, the imperial court theatre, but in practice the work was subcontracted. Music directors, appointed by the Hoftheater, were given responsibility not only for the engagement of the musicians and provision of the music, but also for all other matters connected with the performances and their administration.6 While the music directors themselves frequently composed music for the balls, the sheer volume of music required meant that they also commissioned sets of dances from other composers. The fees paid to composers of the stature of Haydn and Wanhal were presumably higher than those paid to less distinguished musicians, but their dances may well have been an additional drawcard that would ensure the profitability of the ball. The commissioning of Wanhal for the 1792 dances was not due solely to his long-established reputation as one of Vienna’s pre-eminent composers, but also because he was known as a composer of dance music. His activity in this sphere seems only to have begun around 1786, but in the intervening six years he had published nine sets of dances. These are dominated by German dances, although minuets, allemandes and English dances also feature. The dances are composed for a variety of forces including fortepiano and are likely to have been intended for use in the private sphere. [Figure 2]

|

Year

|

Dance

|

Number

|

Scoring

|

Weinmann

|

|

1786

|

Menuet

|

12

|

2v b

|

XVIII:1

|

|

1786

|

Deutsche Tänze

|

12

|

fp

|

XVIII:5

|

|

1787

|

Allemande

|

6

|

2ob 2cor 2v b

|

XVIII:2

|

|

1787

|

Ländlerisch-Deutsche Tänze

|

12

|

vn

|

XVIII:3

|

|

1787

|

Ländlerisch-Deutsche Tänze

|

12

|

2vn

|

XVIII:4

|

|

1787

|

Englische Tänze

|

6

|

fp

|

XVIII:6

|

|

1790

|

Menuet

Allemande |

18

18 |

2fl 2cor 2vn b

|

XVIII:7

|

|

n.d.

|

Englische Tänze

|

6

|

fp

|

XVIII:8

|

|

1792

|

Deutsche Tänze

|

12

|

fp

|

XVIII:10

|

Figure 2: Wanhal’s published dances 1786–1792

While Wanhal might have been busily composing sets of dances for the past few years as well as producing a substantial amount of keyboard music and chamber works, his output of orchestral music had dwindled. He had abandoned composing symphonies by the mid to late 1770s7 and the only works that he had continued to compose that employed sizable instrumental forces were concertos.8 Wanhal’s extensive corpus of sacred music also employs at times quite large instrumental forces, but the dating of many of these works remains highly problematic.9 Thus, the commission to write dances for the Kleiner Redoutensaal not only presented him with an opportunity to return to the field of orchestral composition, but also to write for the largest and most elaborate instrumental forces of his career.

The Großer Redoutensaal employed the largest orchestra in Vienna, numbering 43 players, larger even than the orchestras employed by the Burgtheater and the Kärtnertortheater which typically numbered no more than 35 players. The small ballroom had an orchestra of 27 players but it was no less instrumentally rich.10 Wanhal’s dances, like most of those performed in that venue, are scored variously for piccolo, one or two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets (clarini), timpani, two violins and basso. A small posthorn (Posthörndl) is also employed in the trio of No.12 in the first set of German dances of 1792. The size of the forces available and the flexibility it offered must have been welcomed by Wanhal since it provided the means for introducing variety in genres that offered the composer little or no flexibility. However, as we shall see, the very richness of the instrumentation also presented the composer with a number of unavoidable technical problems, and it is these that give us a glimpse into how the dances may have been performed at the time.

Like all compositions of their kind, the performance of Wanhal’s orchestral dances could take two forms: performance as musical works and as an accompaniment to social dancing. There is evidence that dances were performed in concert before the dancing began. Joseph KarlRosenbaum, a former official at the Esterházy court whose diaries provide a rich source on information about the performance of Haydn’s late works, records in his diary attending a ball on 7 January 1798 where he listened to a performance of minuets and German dances by Fuchs at the beginning of the evening and presumably before the dancing began.11 These ‘concert’ performances of the dances were presumably listened to with some care by the audience. The dances themselves were likely played as written including the conventional observation of repeats. In the second scenario, however, the music itself formed only one part of a more complex public performance. The dancers–and the choreography of the dance–exerted a powerful influence over the act of performance. Individual dances might have been extended in duration through more flexible observation of repeats in order to accommodate the choreography, a practice that would have proven extremely useful given the longstanding convention that dancers could join in at any point as well as reducing the amount of music needed for the evening’s dancing. The instruction to change the pattern of repeats would likely have been given verbally by the leader of the orchestra before the dancing began and it may not have applied to every dance.

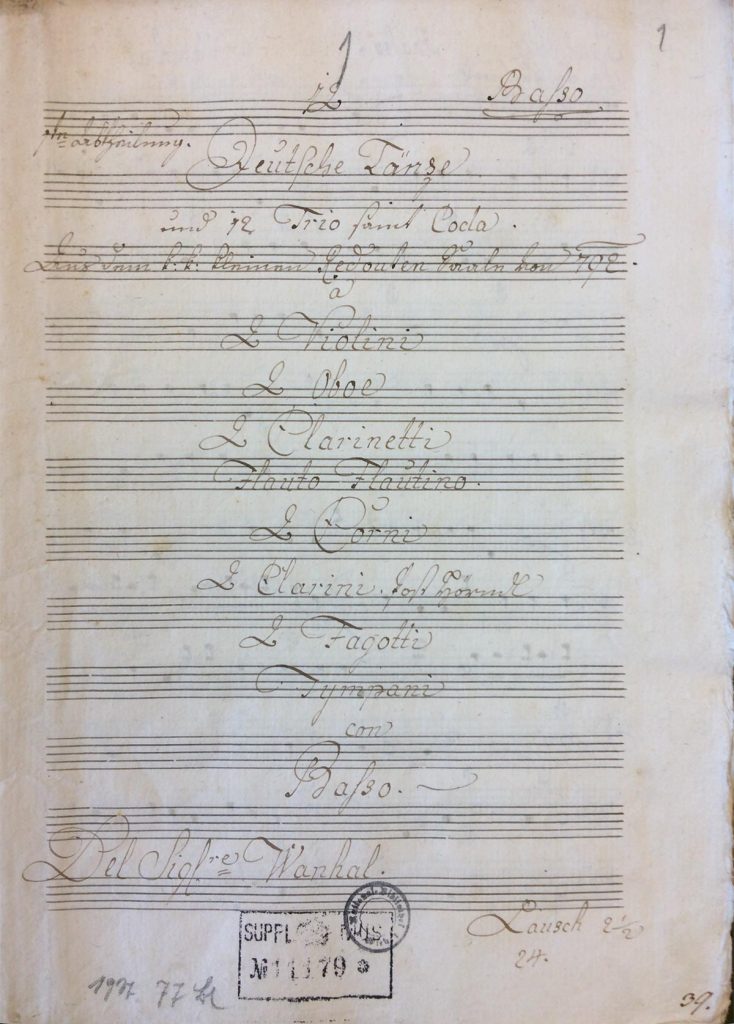

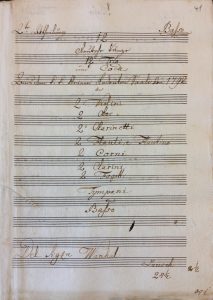

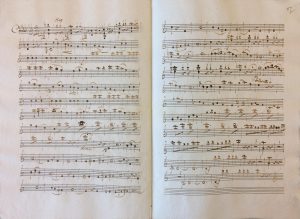

The sets of extant minuets and German dances for the Redoutensäle typically comprise six or twelve dances. Both dances follow the same structural pattern: two sections of eight bars, repeated; a second section–generally, but not invariably labelled Trio–which follows the same pattern, after which the first section is repeated. The majority of the dances close on the tonic at the end of the first section and the trios are largely in the same key as the parent dance. It is interesting to note that in the performance material for Wanhal’s 1792 dances, which consists of two sets of 12 German dances12 and two sets of 12 minuets13, there are no Da Capo markings in the parts. Only in a single instance, in No.11 of the first set of minuets, is there evidence of the first section being repeated: in this case, the music is written into the parts. The description of the two sets of German dances on their respective wrappers also raises an interesting question about the status of the trio sections which are noted on a separate line as if they are independent entities. [Figures 1 & 2]

Figure 3: A-Wn Mus.Hs.11179 “i2 Deutsche i792” (Part 1 Basso, title page)

Figure 4: A-Wn Mus Hs.11180 – “i2 Deutsche in C 1792” (Part 2), title page

The wrappers for the minuets make no mention of the trio sections although they are present in both sets. On the face of it, this seems a relatively unimportant detail; but as other sets of dances in the Kaisersammlung demonstrate, trios were not invariably composed for every dance. In 1790, for example, Johann Baptist Haselbeck, one of the most prominent composers of dance music in Vienna, composed 12 Minuets with 6 Trios for the large ballroom14, while in 1792, Joseph Heidenreich produced 12 German dances with 3 trios and coda which were also performed in the large ballroom.15 If, as this evidence suggests, trios were considered as independent musical entities, then it may well be that our expectation of how repeats were executed needs to be reconsidered.

Of one thing we can be absolutely certain: the dances cannot have been performed seamlessly, each leading into the next dance. Although the sets of Germans dances, particularly those with codas, night be considered antecedents of the later Viennese chain waltzes of Josef Lanner and Johann Strauß I, they were clearly not conceived for continuous performance. That much is obvious from the tonal design of the sets and the implications this has for the performers.

As Table 3 illustrates, all six sets of dances by Wanhal employ a wide range of tonalities, albeit all in the major mode, and none has two successive dances in the same key. Neither does the sequence of tonalities unfold in a consistent intervallic progression. Tonal changes are disruptive and serve as natural divisions between dances. The horns need to change crook for each new dance, and Wanhal specifies the use at various times of clarinets in C, D, A and Bb. The trumpets also need to be re-crooked, but the biggest tuning problem of all applies to the timpani. Unless two or three pairs of timpani were available for the performance, there would necessarily need to be a longer interval between dances to allow the timpanist time to retune.

In the case of Nos 4 and 5 from the first set of 1792 minuets, the timpanist needs to retune from Eb-Bb to C-G in successive dances which must have necessitated a longer break between dances. If we consider these as structural pillars in the sequence of dances, their placement perhaps was intended to serve a practical as well as musical purpose in creating an opportunity for dancers to join or leave the dance floor with minimum disruption.

After the opening dance, the dances scored with trumpets and timpani are most commonly Nos.5, 8 and 12. The minuet referred to above is an anomaly in this respect, but Wanhalomits trumpets and timpani in the final dance. This also the case in the second set of 1792 minuets and its counterpart in the 1794 set. Two other points stand out in relation to tonal design. The first is that Wanhal sets dances 3 and 4, irrespective of genre, in Bb and Ebrespectively in every set, and this pattern is repeated in dances 10 and 11 in all four 1792 sets but is reversed in the dances of 1794.16 In all twelve cases, the first of these keys is preceded by either F major or G major: G-Bb (5), F-Bb (5), G-Eb (2). Why this should be the case is not entirely clear, but the consistency of Wanhal’s tonal choices at these points in the sets make it obvious that it was an integral part of their conception. The second point, is that only two of the six sets of dances open and close in the same key. Wanhal was not setting out to impose some kind of cyclic unity on the sequence of dances. Rather, like all of his contemporaries, his intention was to invest each set with as much variety as its narrow structural and stylistic conventions allowed.

|

Dance |

1792 D1 |

1792 D2 |

1792 M1 |

1792 M2 |

1794 D |

1794 M |

|

1 |

D |

C |

D |

C |

D |

D |

|

2 |

G |

F |

G |

F |

G |

G |

|

3 |

Bb |

Bb |

Bb |

Bb |

Bb |

Bb |

|

4 |

Eb |

Eb |

Eb |

Eb |

Eb |

Eb |

|

5 |

C |

G |

C |

G |

C |

C |

|

6 |

A |

E |

A |

E |

F |

F |

|

7 |

F |

A |

F |

A |

A |

A |

|

8 |

C |

D |

C |

D |

E |

D |

|

9 |

G |

F |

F |

F |

G |

G |

|

10 |

Bb |

Bb |

Bb |

Bb |

Eb |

Eb |

|

11 |

Eb |

Eb |

Eb |

Eb |

Bb |

Bb |

|

12 |

C |

C |

G |

G |

D |

F |

|

Coda |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Figure 5: Minuets and German Dances – Tonalities

D = Deutsche; M = Minuet; tonalities in bold face indicate dances with trumpets and timpani.

The combinatorial possibilities that Wanhal’s enlarged orchestra affords him is exploited to good effect over each set. The brevity of each dance and its trio allows little scope for prominent solo writing, but it does invite Wanhal to play with the composition of the ensemble creating timbral and textural variety. Trumpets and timpani are used sparingly, as we have seen, but so too are other instruments. The scoring of the first set of 1792 German Dances, for example, also makes comparatively little use of the piccolo and flute, reserving them exclusively for solos in several trio movements; the second clarinet, horn and bassoon are frequently omitted in trio sections, a pattern that is also seen in the other sets of dances.

|

No |

Picc* |

Fl |

Ob 1 |

Ob 2 |

Cl 1 |

Cl 2 |

Fag 1 |

Fag 2 |

Cor 1 |

Cor 2 |

Clno 1 |

Clno 2 |

Timp |

|

1 |

|

|

D, T |

D, T |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

2 |

T |

|

T |

D, T |

D |

D |

D, T |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D |

D, T |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

5 |

T |

|

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

6 |

|

|

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

8 |

T |

|

D, T |

D, T |

D |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

|

9 |

T |

T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D |

D, T |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

10 |

T |

T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

|

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

T |

|

D, T |

D, T |

|

|

|

|

12 |

T? |

T? |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T(P) |

D |

D, T |

D, T |

D, T |

|

C |

|

|

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

C |

Figure 6 – “i2 Deutsche 1792 (Part 1)” – Instrumentation

Blank = tacet; D = Deutsche; T = Trio; C = Coda; (P) + Posthörndl

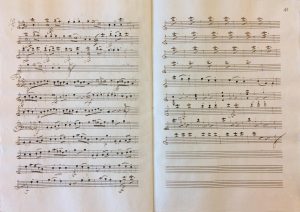

The extant parts also give us a glimpse into how the dances may have been performed. Several parts are assigned to two instruments: Flauto, e Flautino; Oboe, e Clarinetto Imo, Oboe, e Clarinetto 2do. Specification of one instrument or the other occurs exclusively in Trios. Where this does not occur, the parts play in unison unless independent parts are assigned on a two-staff system. These notational conventions tell us that both players performed from the same part: it was employed solely to save paper rather than encourage or permit substitutions. The Posthörndl in the trio of No.12 was clearly intended to be played by the first horn.

Unlike the stylized minuets encountered in symphonies, string quartets and other instrumental genres which many composers seem to have regarded as a challenge to their ingenuity, the composition of minuets for dancing offered little opportunity for flights of fancy. Wanhal’s Redoutensaal minuets are, as one would expect from the composer, attractively written and colourfully scored; they are elegant dances that are perfectly suited to their function and are not without deft and at times ingenious compositional touches. The German dances, to a large extent, exhibit the same qualities, both positive and negative, on account of the constraints placed upon their composer to accommodate the needs of thedancers. However, unlike the minuets, all three sets of Wanhal’s German dances conclude with a coda which affords him the opportunity to exercise his powers of musical inventionwith considerably greater freedom.

Most codas in sets of German dances contain within them unambiguous allusions to themusical structure and style of the dance that sits alongside more obvious closing material, but their placement in the coda varies considerably from set to set as Wanhal’s dances demonstrate. The proximity of these references to the final dance in the set has obvious implications for the extension of the dancing.

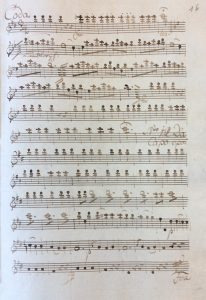

Figure 7: A-Wn Mus.Hs.11179 – “i2 Deutsche i792 (Part 1)”, Violino I, Coda

The coda to Wanhal’s first set of German dances composed for the 1792 season begins with an anacrusis which suggests that it follows on directly from the repeat of No.12. It opens withmaterial that closely resembles the first half of a German dance: the eight-bar section–which includes a medial cadence in the dominant–is first performed forte and repeated at the pianolevel with no change in orchestration. The second statement of the theme cadences into a new section which is characterized by more vigorous, ‘symphonic’ writing. Once again, thissection unfolds in symmetrical patterns but there is a greater sense of expansiveness in the music. The medial cadence–on the tonic–occurs at the end of the eight-bar phrase, and the second phrase, which is more obviously cadential in purpose, is repeated at the piano level. The second four-bar sub-phrase, however, is now substantially rewritten and expanded to elide into an extended closing section of 28 bars consisting largely of a series of powerfully-scored cadential units in which the horns and trumpets are prominent. Over the course of the coda, the music shifts in style from dance-like to symphonic and with it, its function in terms of social dance changes.

Figure 8: “12 Deutsche in C 1792 (Part 2)”, Violino I, Coda

Wanhal’s second set of 1792 German Dances has a substantially longer and more complex coda than its partner. Unlike the coda to the first set with its possible link to the final dance, the multipartite, through-composed second coda gives no such impression. It begins in the same tonally ambiguous fashion as Beethoven’s First Symphony with a cadence on the subdominant (V7/IV–IV) before establishing the tonic with a conventional V-I progression. This pattern is repeated and then links into a lengthy, powerfully scored passage which functions not as a coda but rather as an introduction: it even culminates with a dotted minim with fermata, with the additional marking “tenu” in the parts. This entire section is 53 bars long, which, given the scale of the preceding dances, establishes its musical importance. After the fermata, Wanhal introduces a new German dance, but this time, it is through-composed rather than employing notated repeats. There is, however, no equivalent trio section: what follows is another elliptical affirmation of the tonic, this time via the supertonic (V/ii–ii – V–I). After a surprising and disruptive fermata, a six-bar lyrical cadencing phrase leads into a repetition of this harmonic sequence complete with fermata. The lyrical passage returns and leads into the final phase of the 139-bar coda with its energetic cadential figuresand prominent fanfares.

If the coda to the first set of German dances shifted from dance music to the symphonic, the second coda might be thought of as a microcosm of the entire ball from its brilliant introduction, charming dance music and thrilling conclusion. In the German Dances of 1794,Wanhal experiments once again with the structure of the coda.

Figure 9: A-Wn Mus.Hs.11181 – “i2 Deütsche in D…1794”, Violino I, Coda

The link between the coda and the last dance is particularly strong in this final set. Its opening two bars replicate the close of dance No.12, but the prominent repeated Ds in the first violin and other parts are now reharmonized in B flat major, with bars 3–7 underpinned by a 6/5 chord. The fermata in bar 7 serves a functional purpose as well as a dramatic one since the horns need to change from a D crook to a B-flat crook for the section that follows. This is once again a dance which is labelled “Ländlerisch” in the parts, presumably on the authority of Wanhal himself. Unlike the dance-like sections in the 1792 codas, this dance is written in exactly the same manner as the twelve dances that comprise the main body of the work; that is, in two sections with notated repeats. At the conclusion of the second half of the dance, Wanhal returns to the opening material which is now extended from seven bars to thirteen and modified to end on V7/III. The significance of this harmony is emphasized by the fermata and the realization that its function is to prepare for the unexpected return of dance No.12 which, incidentally, requires the horns to return to using D-crooks. At the conclusion of No.12, which was presumably played with the trio and all repeats, a 40-bar closing section brings the coda to a close. Unlike the bombastic conclusions to the 1792 German Dances, Wanhal, so often the master of surprise, brings the works to a pianissimo close.

There are two very obvious opportunities for the dancing to continue in the coda to the 1794 dances albeit they are separated by independent material. But did the dancing continue? It is possible, but such attempts would surely have ended in chaos given the unpredictable structure of the coda. The same applies to the codas to the 1792 sets, and so the question must be asked: if the symmetry breaks down and music cannot be danced to, for whom were the codas composed? The likely answer is that they were written for the dancers and the listenersjust as the masquerade balls were not attended solely for the purpose of social dancing. The unpredictable nature of the codas with their veiled allusions to the dance, might be thought of as a musical analogue of the masquerade balls themselves where the patrons delighted in concealing their identities from their friends and acquaintances with varying layers of disguise. As such, Wanhal’s German Dances, are perfect expressions of late eighteenth-century Viennese dance culture.

- Under the terms of the decree, masquerade balls were permitted during the carnival season that ran from Epiphany (6 January) to the beginning of Lent. Two to three masked balls (Redouten) could be held weekly during this period, lasting from 9pm to 3am, and until 5am after 7 February. See Erica Buurman, The Viennese Ballroom in the Age of Beethoven (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 11.

- Joonas Korhonen, ‘Urban Social Space in the Development of Public Dance Hall Culture in Vienna, 1780–1814’, Urban History, Vol.40 No.4 (2013), 610-611

- Reingard Witzmann, Der Ländler in Wien: eine Beitrag zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Wiener Walzers bis in die Zeit des Wiener Kongresses (Vienna: Arbeitbeitstelle für des Volkskundealtlas in Österreich, Bd.4, 1976)

- [“… in jedem [Saal] ist ein besonderes Orchester, das abwechselnd immer eine Stunde lang Minuets, und eine Stunde lang deutsche Tänze spielt”.] Johann Pezzl, Beschreibung der Haupt- und Residenz-Stadt Wien (Vienna, Carl Armbruster, 1820), 297

- Buurman, op. cit., 28

- Buurman, op.cit., 20.

- Paul Bryan, Johann Wanhal, Viennese Symphonist: His Life and His Musical Environment, (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1997).

- Allan Badley, ‘Chronological Signifiers in the Concertos of Johann Baptist Wanhal’ Radovi Zvavoda za znanstveni rad Varaždin, No.25, 2014. https://hrcak.srce.hr/131767

- Halvor Hosar, ‘His Name Immortal: Five Studies on the Sacred Music of Johann Baptist Wanhal’. PhD thesis, University of Auckland, 2019.

- Buurman, op.cit., 17

- Buurman, op. cit., 27

- A-Wn Mus.Hs.1179: “Basso / i2 / 1te Abtheilung / Deutsche Tänze / und i2 Trio samt Coda. / Aus dem k: k: kleinen Redouten Saaln von [1]792. / a / 2 Violini / 2 Oboe / 2 Clarinetti / Flauto Flautino. / 2 Corni / 2 Clarini. Post hörndl / 2 Fagotti / Tympani / con Basso / Del Siglre Wanhal”; A-Wn Mus.Hs.1180: “2te Abtheilung Basso / i2 / Deutsche Tänze / i2 Trio / und Coda / Aus dem k: k: kleinen Redouten Saal von i792 / a/ 2 Violini / 2 Oboe, / 2 Clarinetti / 2 Flauti, e Flautino / 2 Corni / 2 Clarini / 2 Fagotti / Tympani / e / Basso / Del Sigre Wanhal / Lausch / 2 ½ /24 ½ / 39 ½”.

- A-Wn Mus.Hs.11312: “i2 / Menuetti / i792/ aus dem k: k: kleinen Redouten Saal / à Violini due / Oboe Flauti due / Clarinetti due / Fagotti due / Corni due / Clarini due / Tÿmpani / è / Basso / Del Sigl: Giovani Wanhal”; A-Wn Mus.Hs.11313: “i2 / 2te Abtheilung / i792 Menuetti in C / aus dem k: k: kleinen Redouten Saal / à / Violini due / Oboe Flauti due / Clarinetti due / Fagotti due / Corni due / Clarini due / Tympani / Basso / Del Sigl. Giovanni Wanhal”.

- A-Wn Mus. Hs. 12967: “12 Menuetti, 6 Trios (in D). Aus dem k.k. Grossen Redoutensaal 790 per il Clavicembalo” (transcription).

- A-Wn Mus. Hs. 11140: “12 Deutsche Tänze [in D], 3 Trio und Coda: a 2 Violini, 2 Oboe, 2 Clarinetti, Flauto, e Piccolo, 2 Corni, 2 Clarini, 2 Fagotti, Tympani, Basso. Aus dem K: K: grossen Redouten Saale 1792”.

- A-Wn Mus.Hs.11181: “i2 Deütsche in D: aus dem K: K: keinen Redouten Saaln für das Jahr 1794. / a. / 2. Violini / 2. Oboe. / 2 Clarinetti / 2. fagotti / 2. Corni / 2. Clarini / Tÿmpani / Flötin et / Basso. / Del Sigl: Wanhal”; A-Wn Mus.Hs.11314: “12 Menuetten in D: aus dem K: K: kleinen / Reduten Saaln für das Jahr i794. / 2 Violini / 2. Oboe / 2. Clarinetti / 2. Fagotti / 2. Corni / 2. Clarini / Tÿmpani / Flauto et picolo / et / Basso / Del Sigl. Wanhal”.